Natural fabrics, and silk in particular, have some amazing properties that have been adapted for many uses, one such being the manufacture of parachute canopies. You would think that the stringent requirements of a parachute fabric would preclude any other use, not so. During the 40 and 50’s the versatility of both the silk fabric combine with resourcefulness of a generation of ladies allowed their reuse for ‘big day’ dresses – recycling at its best.

History of the Parachute

12th Century: Evidence of parachutes exists as early as the 12th Century, where the Chinese were using a rigid structure, similar to a parasol, as part of circus entertainment.

12th Century: Evidence of parachutes exists as early as the 12th Century, where the Chinese were using a rigid structure, similar to a parasol, as part of circus entertainment.

15th Century: An unattributed Italian manuscript from the 1470s is the first record of what we would recognise as a parachute, and this was following by a sketch by Leonardo da Vinci in 1495. This simple sketch showed a pyramid structure holding open a gummed linen cloth for use to escape from a building. There are no records of it having been made and tested, but it was proved a viable design in 2000.

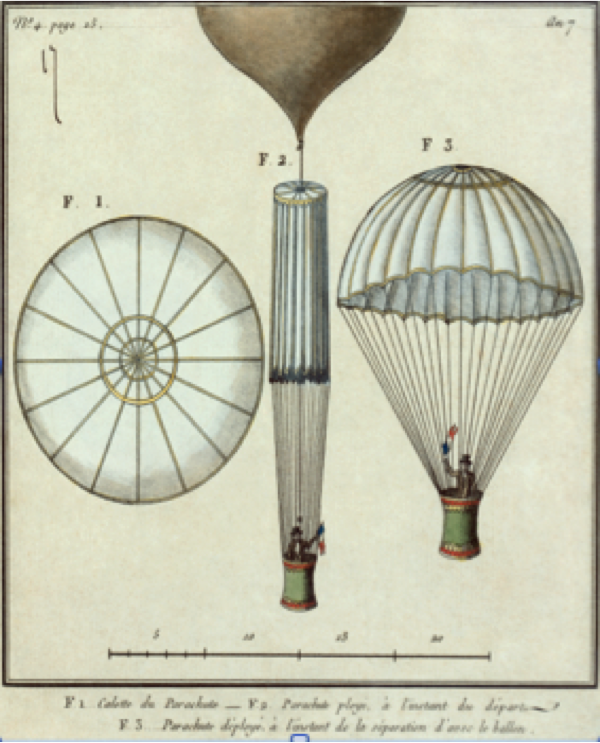

18th Century: Development of parachutes then seemed to stall until the late 18th Century when the French fashion for hot air ballooning allowed interest in parachutes to gain impetus. Both Joseph Montgolfier and Louis-Sebastien Lenormand made successful jumps using fixed parasol structures, the latter from the Montpelier tower.

Another preeminent balloonist of the time, Jean Pierre Blanchard, became interested. Between 1797 and 1802 Blanchard made numerous jumps from hot air balloons, at altitudes up to 2400m, and is attributed as coining the word parachute derived from the French paracete (protect against) and chute (fall).

Two further developments progressed parachute design in the 18th century: canopy venting, which reduced canopy oscillation, and the collapsible parachute, which maintained its structure by air pressure alone. These culminated in 1887 when Thomas Baldwin introduced the vented collapsible silk parachute in America.

20th Century: At the turn of the 20th Century the arrival of the aircraft, as with hot air balloons, spurred on development of parachutes. Significant milestones during this period are the opening of the chute using a ripcord in 1908; the patenting of the pilot chute in 1911; and the first moving aircraft jumps by Grant Morton 1911 (held chute) and Albert Berry 1912 (attached chute).

At the start of the First World War, balloon and aircraft pilots were not supplied with parachutes. These were gradually adopted, initially by the Germans, with the first recorded escape from a damaged aircraft being in 1916 by an Australian pilot on the Russian front. By World War II they were in universal use by pilots, paratroopers and for equipment deployment.

Fabric of choice

Parachute material has to possess a wide range of properties with weight, tear resistance, elasticity and air permeability being central. A variety of fabrics were used in the parachute’s development, but the ability of silk to meet all the requirements meant it became the fabric of choice for parachutes between 1900-1945.

Silk’s excellent strength-to-weight ratio, when combined with its inherent elasticity, allowed production of a lightweight but incredibly strong canopy. With comparable strength to steel and some 10 times stronger than nylon, silk parachutes easily absorbed the shock loadings during opening. Silk also has excellent tear resistance in a plain or mock leno weave and when combined with the correct seam angles tears that could lead to a fully ruptured canopy were avoided. The plain and mock leno weaves fortunately also had the correct air permeability, controlling the pressure differential across the canopy, thus happily not affecting the rate of decent.

‘Big day’ dresses from silk parachutes

Before WWII, Japanese Habutai Silk was the optimum silk for parachutes. The war led to a silk shortage in other parts of the world, and forced investigations into other fabrics and ultimately the use of Nylon, which had even better elastic properties, did not succumb to mildew and, perhaps more importantly, was less expensive than silk.

It was the very same silk shortage that led to the reuse of the surplus parachute silk into other items of clothing. From about 1945, there are reports of women fairly frequently turning silk parachutes sent by loved ones back home or captured from downed enemy airmen into underwear and wedding dresses.

Although requiring a high level of seamstress skills and an element of dedication to dissemble the canopy, many were turned into stunning ‘big day’ dresses during a period of hardship and rationing.